Eyes Closed Listening

I’ve always had something of an issue with eyes closed listening. It reminds me of being a kid and being told we must close our eyes to pray or give grace at the dinner table, something I thought was a very strange idea. I refused to do this and instead watched everyone around me praying with eyes shut. Why would closing your eyes lead to one being closer to this god, what is it about the visible world that is so offensive to this god and why is it ok to make and hear sound and smell the food in front of us?

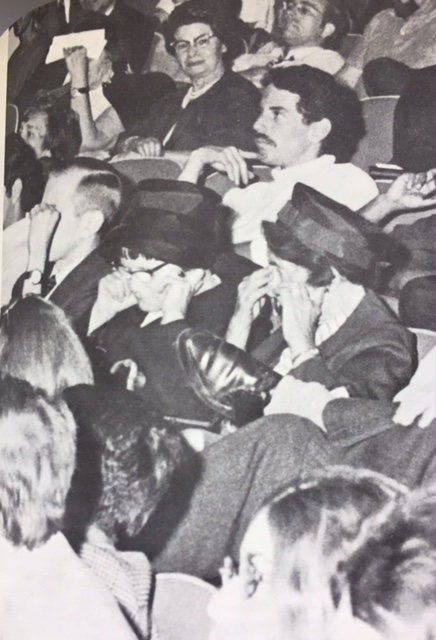

At a conference in Leiden last week I felt a similar confusion over the listening practices of many of those in attendance. Music and sound works were played and the congregation dutifully closed their eyes, one member even clasped his hands and rested his forehead on them. I watched the pious action of listening in this situation with confusion and similar to when i was a child, I was interested in watching these people who could not see me watching them, all the time wondering what was so bad about the visual that it needed to be shut down to truly hear the sounds being presented to us.

At one point, Edwin van der Heide asked for the windows to be opened in an attempt to give a sense of the surrounding everyday sounds that would have been present in the original outdoor installation. Outside was very chilly and the room quickly became uncomfortably cold. While the recording played many of the same people who had previously sat with their eyes closed now looked outside, connecting the various sounds they could hear with what was making them. There was some sort of shift here whereby recorded art sound needed reverential listening while the everyday sounds could be looked for in the visual.

The second mode of listening I saw was eyes closed and fingers pressed firmly into ears. I’m very unclear what such an action symbolises but it is certainly very different to the religiosity of closing ones eyes.

(image taken from Beyond the Dream Syndicate, p281)

Lost in text

It’s been quite a while since I’ve posted a blog! For the most part this is due to spending all my writing energy writing my next book Gallery Sound, which I am happy to say is now with the publisher.

So I plan to write down some thoughts here over the summer and post them here, so expect a few more posts than in recent months!

Janet Cardiff and Christina Kubisch

I’m currently working on a sound/audio walking section for Gallery Sound. While researching the section I have discovered a curious abnormality (if that is the correct word) in the scale and publishers of the scholarship on Janet Cardiff and Christina Kubisch.

To put it bluntly, there is vastly more written about Cardiff than Kubisch. Cardiff has numerous catalogues, scholarly (read peer reviewed) journal papers and many entries in art magazines. Kubisch has very little of anything. What is more confounding is Kubisch for the most part is discussed in new music / computer music journals, namely Leonardo Music Journal and Organised Sound. When a search is conducted in Artforum I found 20 entries for Cardiff and only 6 for Kubisch.

Given Kubisch is some twenty years older than Cardiff and given that both artists have a serious reputation, why is it that Kubisch has not sparked scholarly nor art world discussion while Cardiff has. Why is it that authors writing for media based music journals have an interest in Kubisch?

I really don’t have an answer except to posit a link with the German language. Perhaps there are numerous German language publications dedicated to Kubisch? Whilst a visiting professor in Berlin I had the opportunity to witness a discussion with Kubisch and I was very excited to here her talk. However, the discussion was held solely in German so I was disappointed to not be able to follow what was being said and contented myself with her performance. I noticed while in Berlin that many music events were conducted in English yet this and a few other more scholarly events were given in German. Could this be the reason for Kubisch’s relative obscurity?

Topsy-turvey historical continuums and mimetic fissures

In an editorial for a recent edition of Organised Sound, Salomé Voegelin and Thomas Gardner make a peculiar pronouncement that, “the current prominence of sound art has been aided by its relationship to visual arts practice and its discourse, but that even as this visual affiliation has promoted sound art’s recognition, making it more visible, it has also obstructed the discussion of its sonic materiality and processes and has neglected its musical heritage and those aspects of its practice that recall that history.”

This is a rather bizarre statement for a number of reasons, not least the idea of a prominence of sound art. But what really struck me was the idea that sound art has been aided by the visual arts to the point where the visual arts have actually obstructed the forms musical heritage.

In a previous blog I voice an objection to the continual attempts to situate composers within discourses of sound art and so it will be no surprise that I am bewildered by the claim of visual arts dominance in the discourses of sound art. This is not helped by the editors writing in a very general and vague manner – they do not point to what texts they feel neglect music, nor what texts favour the visual arts (let alone contemporary art) so it is hard to judge the background for their reading. Also by not giving examples of either texts nor the artists/musicians/directors/authors we are left to wonder what exactly they are discussing.

Part of the problem lies in the author’s reliance on outdated terminology. The use of ‘visual arts’ has wained, replaced by contemporary art in most critical circles (at least when describing art from post-1989). Contemporary art takes everything within human experience to be available as the content of art and thus music is completely available as a medium and as the content of contemporary art. It could be argued that this strategy has the effect of de-historicising music but this would not be an argument for discourses of sound art nor the sonic arts as they do not have such an all encompassing disciplinary model.

The idea that discourses in sound art, or event the sonic arts, have not paid enough attention to musical discourse does not make any sense to me. The key figures who are time and again referenced, cited, name-checked, copied and plundered in the name of sound art are for the most part composers, namely John Cage, Alvin Lucier, La Monte Young, Pierre Schaefer, Pauline Oliveros and so on. The developing cannon of sound art and already prominent in the sonic arts is represented almost completely by composers. Just what texts are the editors thinking of?

European Spring

This year is turning into a very eventful one. At the centre of this will be three months in Berlin where I will be the Edgard Varèse Guest Professor at the TU Berlin – https://www.ak.tu-berlin.de/. While there I will be running two graduate courses, Sound in Music and Art, and Sound and Materials.

I’ve also lined up a number of talks, the first is at Goldsmiths 17th April – http://www.gold.ac.uk/, followed by talks at the University of Amsterdam, Tromsø – http://digitalmedia.wikidot.com/encode-lectures, and Cambridge.

Of course while in Berlin I will be working away on the Gallery Sound book and posting plenty of blog entries.

More research surprises: installation, sound art or music?

Last week I spent time looking at Alvin Lucier, for the same chapter as Young.

The surprise takes the form of how many of the few words written about Lucier have been wrestling with his compositions as being music (or not music). This stems from a very conservative view of music held by recent writers intent on defining sound art. Having trouble taking Lucier’s work at face value, as composed music, they try to prove it is installation and therefore indebted to visual art practices, or that it is sound art, a term not used at the time of the works most often discussed.

The bizarre and banal argument that Lucier’s work looks like other forms and thus requires a reappraisal is fundamentally flawed. Within art we expect practices to be influenced by multiplicity of forms, it openly takes elements of theatre, performance, literature, media, TV, the Internet, music, games and so on. We wouldn’t look at contemporary art that uses pop music, for example, and try to claim it isn’t art but instead needs to be rethought as music, yet when Lucier’s music takes on elements of non musical form there is a call for rethinking. Music post-cage can include anything. Including anything means…. um…. including anything. Music can look like installation, it can look like theatre, it can look like bird watching. It can even include sound!

There is no need to waste any more time arguing for its reading as sound art or installation. Now can we get onto appraising the work for its content, its history and its influence on contemporary practices?!

La Monte Young’s empty but full gallery installations

Carrying out research for Gallery Sound on La Monte Young is an eye opener. I was surprised, if not shocked, with the lack of materials published on the composer. However we look at it Young has been influential on the generations of minimal, drone and long duration composers that came after him. He is also named checked by many gallery artists working with drones and long duration installations.

While he is regularly cited as influential exactly what is being cited is unclear. There are only a couple of published books with Young’s name front and centre, Sound and Light: La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela and Draw a Straight Line and Follow It: The Music and Mysticism of La Monte Young. There also exists an unpublished phd (written by Peter Blamey) and a few discussions within books on minimal music. This lack of critical writing can he held up against another artist I am researching Bruce Nauman, whom has had thousands of pages inked about his diverse and expansive practice. I could posit that this occurred because Young’s practice is anything but diverse, his practice is one of complete focus on the almost singular task of creating an eternal music from very few parts. Projects last for decades [or eternity] and perhaps critics have found it difficult to have much to say about such a singular and minimal process.

For now La Monte Young’s work is appearing in a chapter entitled “The Empty Sounding Gallery” and the section on the composer will focus solely on the Dream House, a work that was begun in theory around 1962, and one that continues to this day.

Wolf Notes

I have recently written a piece for Wolf Notes about representation. The piece asks questions regarding the strategies for the display of field recordings within the environment of the art museum or gallery. Specifically about representation within field recording. I have been wondering for a long time, why field recordings have been performed in an art context. To me if they are to be presented within this context then questions that are normally posed to art works here need to be posed to the recordings. These questions seem hard for many recordists to answer, especially the conceptually driven ones.

There’s even a bit of philosophy of sound in there too!

Take a read here and feel free to respond through this forum.

Sound Literacies

My blog has been a little neglected over the past few months – this doesn’t mean I haven’t been working on a number of projects, one of which is the subject of this post.

I’m speaking at the Cultural Studies and the New Uses of Literacy Symposium on the topic of ‘sound literacies’ – a twist from the usual visual/digital literacies discussions. The paper is entitled ‘Listening: the practice of close listening in sound culture’ and comes from thinking around what we can learn from art and music’s approach sound literacies.

At its core is a discussion about two fundamentally different practices of the ‘sound walk’. The first comes from 1960s experimentalism (on the John Cage trajectory) via Max Neuhaus and his work Listen (first performed in 1966). Originally performed by Neuhaus by stamping the hands of his audience with the word LISTEN before leading them around Manhattan. Here the composer understands all sounds to be music and thus anything heard during the walk is music.

Quite some years later another form of sound walking was devised by R. Murray Schafer and the acoustic ecology crew. Within this approach the listener walks around a new or unknown environment listening to the local soundscape.

These two tacks, of what seems very similar, are fundamentally different in respect to listening. One is open to all sounds and is using an experimental process to compose, the other is listening to an environment for clue to its acoustic ecology.

For the conference paper I am interested in these two trajectories and where they have taken us. The sound walk itself has become a fixture at sound festivals and conferences (such as Tuned City) and the purpose of such walks has always been unclear to me. I end the paper with a discussion of Akio Suzuki (something I will save for another post).

Noise in the Garden

Contemporary Art & The Noise of TENDING

By Caleb Kelly & Ross Gibson

It’s been a long time coming, but finally a paper I wrote with Ross Gibson has been published in the online journal Interference. I had originally seen a call for an issue of the journal dedicated to ‘Noise’. On seeing this I took a deep breath, wondering why a journal would dedicate an issue to noise at this time. Mostly this wonderment was because noise keeps on coming back as a topic for discussion represented by the same names of the noise cannon. The call-out however stated:

‘… we invite papers that deal not only with categories of aesthetic dissonance or vibrational force, but invite an expanded view of noise as a collection of sonic strategies that engage social, technical, political and economic concatenations.’

I imagined how noise theory and my expansive history in noise (from putting on gigs for Merzbow or Whitehouse, to writing about it in my books and curating it into exhibitions) could be used to read something that might not seem very noisy; namely the garden project at the Sydney College of the Arts entitled TENDING. TENDING, as you can read about, was a very political and noisy project – the signal filled with the noise of beautrocratic interests. Interestingly the process of writing a paper about noise in a garden caused editorial noise. The readers had trouble hearing noise in our paper and keep looking for sound art where there wasn’t any. They wanted to read the inclusion of the 80s noise cannon and connect gardening to sonic art. We, however, wanted to use noise to read the gardening project, to see if our understanding of noise could be used to understand a socially engaged art practice and the complexity of its situation. I see this as a future approach to sound studies, something beyond the often myopic readings of sound pitted against the visual.

In the coming months I plan to expand this approach to see how hearing can help understand things that are seemingly sound-less.